Our project centres on Cyprus, as microcosm for the historically and geo-politically complex wider area of Eastern Mediterranean. At the intersection of 3 continents, Cyprus has been exposed to multiple waves of rule and/or influence from all over the Mediterranean and beyond (including Mycenean, Phoenician, Egyptian, Assyrian, Persian, Macdeonian, Roman in classical times, and Frankish, Venetian, Ottoman and British in medieval to Early Modern and Modern times). This has lead to a very complex cultural and linguistic history. We ask: to what extent has this left traces in speech patterns in contemporary Cyprus? In particular, we investigate the effects of contact bettwen Cypriot varieties of Greek, Turkish and Arabic, which reportedly sound similar in some features (particularly prosody), despite being from different language families and therefore typologically very distinct

Linguistic Diversity

Contemporary Cyprus is a multilingual space. The official languages of the Republic of Cyprus are Greek and Turkish, with Turkish also recognised as the official language in the 'Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus.' While non-Cypriot varieties of these languages are taught in schools and used in certain contexts, the everyday spoken languages are Cypriot Greek and Cypriot Turkish. Thus there is complex diglossia, with 'standard' varieties and Cypriot varieties both existing on a dialect continuum. In both cases, exposure to non-Cypriot, 'standard' varieties is ongoing and influential.

Cypriot Greek is loosely classified as belonging to the south-eastern Greek dialect group, having evolved from Hellenistic Greek in relative isolation from other dialects. It is structurally 'conservative', e.g. retaining medieval morphosyntactic features (e.g. wh clefts), and southeastern phonetic features (e.g. affrication/fronting of palatal fricatives, prenasalisation of plosives). It has also been exposed to significant unfluence from the languages of various waves of colonisers (e.g. Turkish, Middle French, English). Priot to the events of 1974, Cypriot Greek was also used by many Turkish Cypriots (in some case as their only languages). While regional varieties exist, differences have been attenuated by ongoing going processes of levelling and the emergence of a pancyprian koiné.

Cypriot Turkish dates back to the introduction of Turkish to Cyprus during the Ottoman conquest (from 1571), following which it became increasingly isolated from other varieties of Turkish, and subject to heavy influence from Cypriot Greek (and also, later on, English). As a variety of Turkish it is relatively under-studied, but displays distinctive phonetic, morphological and syntactic features, e.g. voicing of word-initial plosives, distinct tense forms (Kappler & Tsiplakou), SVO, Cypriot-specific use of particle mIş (Demir, 2003; Johanson, 2002), focus and wh clefts and rightward subordination (Kappler, 2008). While little known about regional varieties, levelling is likely. Ongoing exposure to non-Cypriot varieties of Turkish occurs through the media, but also through interaction with settlers from Turkey since 1974.

Minority and other languages

Besides these widely spoken, official languages, several minority languages are also spoken in Cyprus (bilingually with Cypriot Greek and/or Cypriot Turkish), including: Western Armenian (@3000 speakers; present since 6th century; language of instruction in some schools) and Kurbetcha (the language of @500-1000 Cypriot Roma, mostly residing in the north). In addition, there are significant expat communities of speakers of foreign languages, such as English and Russian. Having been officially used under British Rule, English is also taught in schools and widely known as an L2 acoss the island.

Of particular interest to our project is Cypriot Arabic. This is a highly endangered language, spoken by around 900-6000 members of Catholic Maronite community, the ancestors of whom first arrived from the Levant in 7th -13th centuries. Having evolved from a hybrid of eastern Arabic dialects, it shares features with Levantine and North Mesopotamian dialects of the Levant. It evolved as a purely oral variety of Arabic, in virtually complete isolation from other Arabic dialects after the 12th century, and has been very influenced by intense and continuous contact with Cypriot Greek (Trudgill & Schreier, 2006). It is reported to be all but unintelligible to speakers of other Arabic dialects. Until 1974, most speakers lived in Kormakitis area (north coast, now under Turkish control), but most now live in the south (although many maintain regular contact with relatives still in Kormakitis, where regular cultural activities take place).

Geography and Internal Displacement

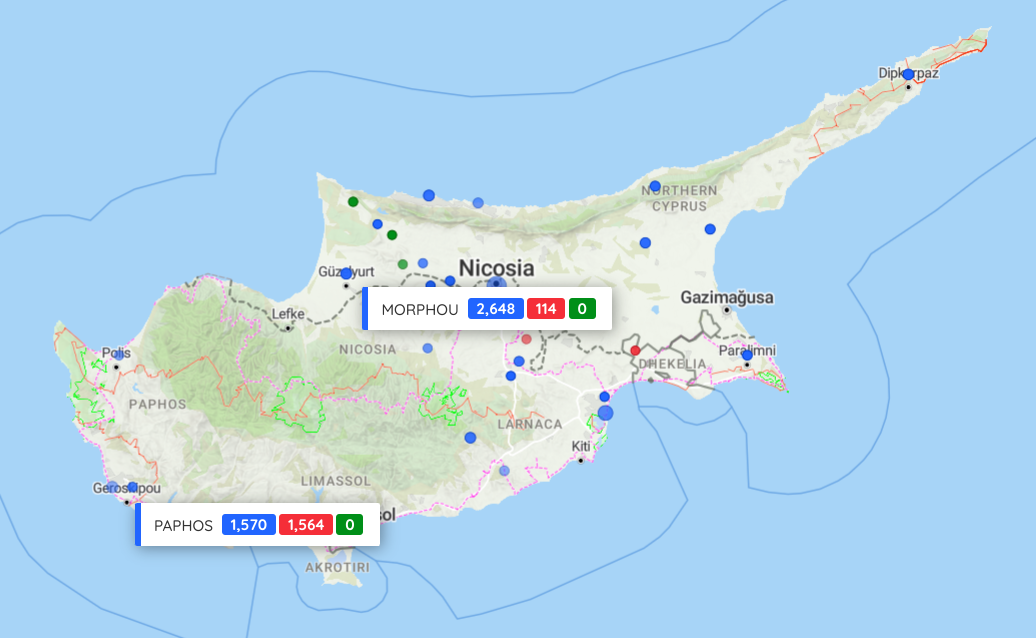

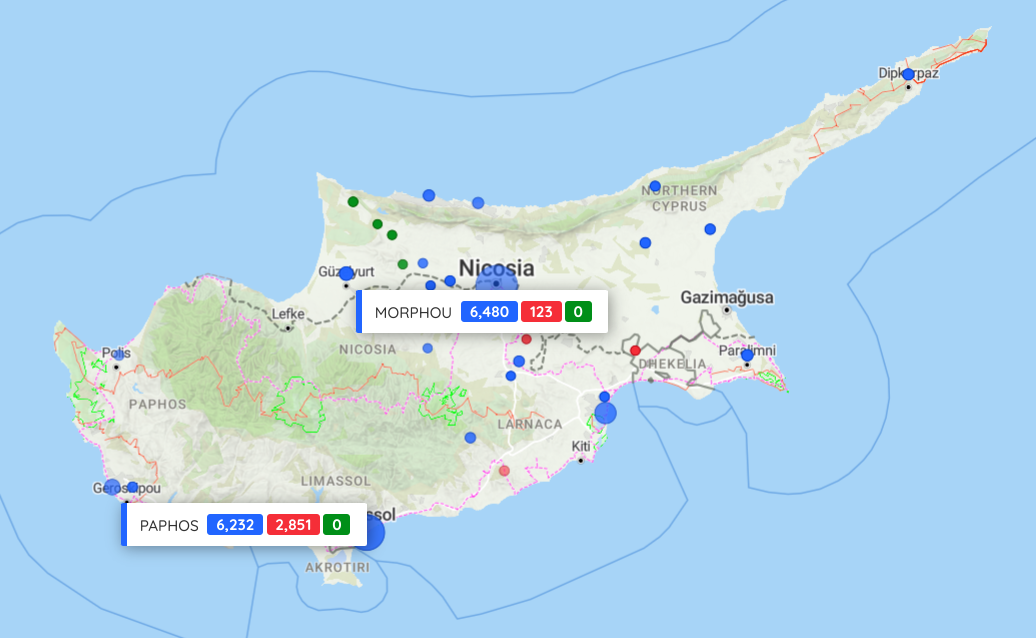

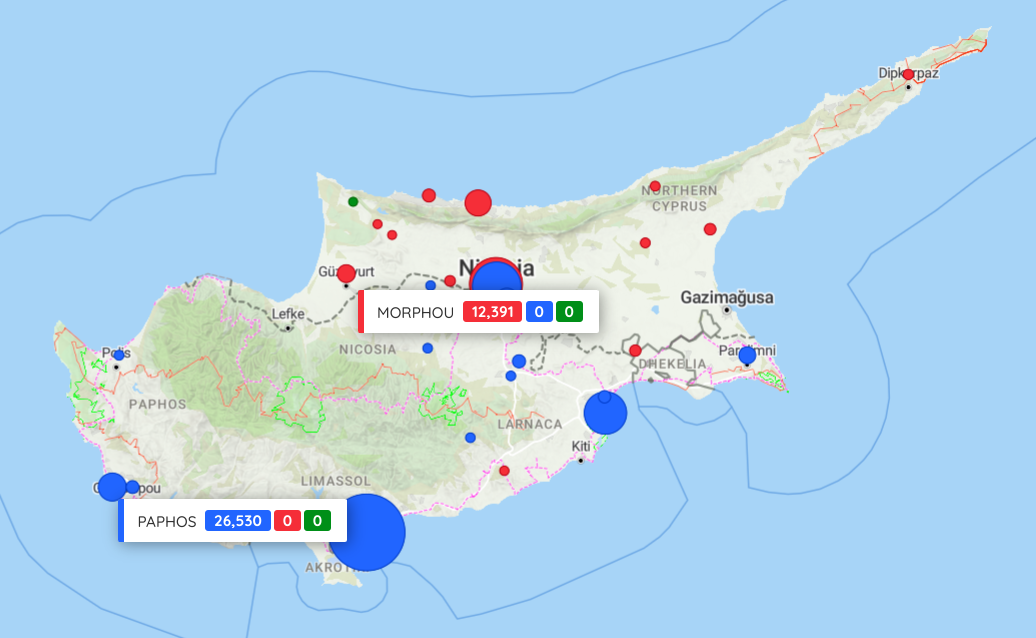

Cyprus has a varied geography of linguistic and ethnic groups, which has also been in flux diachronically, as the figures below show. Before the events of 1974, many villages were ethnically and linguistically mixed, with varying degrees of societal multilingualism. Precise numbers of speakers of different languages, and their relative proportions, have varied with time, as the figures below show. In the figure on the left, we can see that in 1901, Morphou (in the north) is predominantly Greek-speaking, while Paphos is equally Greek- and Turkish-speaking. By 1960 (see middle figure), Morphou has almost tripled in population, but is still predominantly Greek-speaking. Paphos, which has also tripled in population, but is, in 1960, now predominantly Greek-speaking.

|

|

|

|

In 1901, Morphou is predominantly Greek-speaking. Paphos is equally Greek- and Turkish-speaking. |

By 1960, Morphou is still predominantly Greek speaking, while Paphos is now more Greek-speaking than Turkish-speaking. |

In 2001, Morphou is now completely Turkish-speaking, and Paphos is completely Greek-speaking. |

After the events of 1974, Cyprus divided into two linguistically near-homogeneous areas: Turkish-speaking in the north and Greek-speaking in the south, with very little contact between the two languages. As the figure on the right shows, by 2001, Paphos, which has yet again tripled in population size, is now completely Greek-speaking, while Morphou, which has also continued to grow, is now completely Turkish-speaking. Thus after centuries of very close contact (creating the conditions for a Cypriot prosodic melting pot), there have now been some 50 years of linguistic segregation. At the same time, there has been continuing influence of non-Cypriot varieties of Greek and Turkish on the two respective languages, and processes of dialect levelling due to e.g. urbanisation and other sources of demographic shift.